In the old world, you bought customer service software the way you bought office chairs: count the people, count the seats, sign the contract, and move on with your day.

Now we’re being asked to count “seats” for things that do not sit, do not sleep, and do not complain about lunch breaks. Which is convenient for procurement, right up until it isn’t.

Because once AI agents take a meaningful slice of work away from humans, the per-user-per-month model stops being a pricing mechanism and starts looking like a small accounting fiction everyone has agreed not to mention. As Zeus Kerravala from ZK Research puts it:

“It’s not really a virtual agent, it’s just a computer program. So charging by utilization, I think, is the fairest way to do it.”

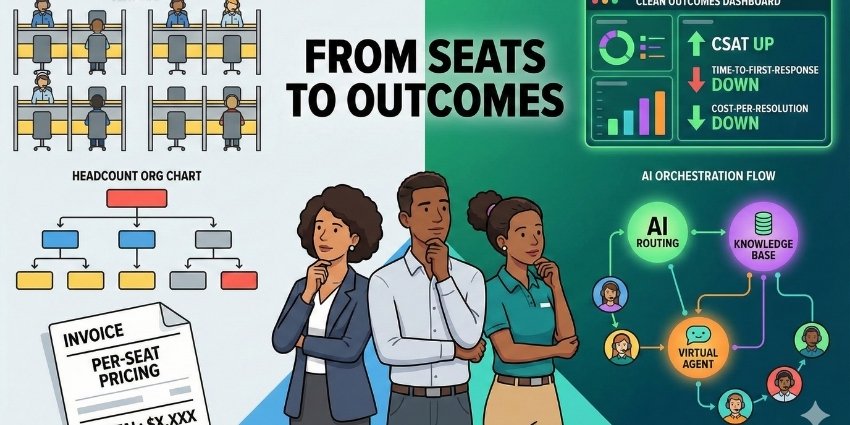

Per-seat pricing has underpinned UCaaS and CCaaS for years, but it is becoming misaligned with how contact centers now operate. As AI agents handle a growing share of customer interactions, enterprises can increase service capacity without adding human headcount, which undermines the logic of paying “per agent.” This shift affects enterprise buying committees, vendor economics, and even investor confidence, because the unit of value is moving away from seats and toward usage and outcomes.

Why “AI Agent Seats” Break the Per-Seat Pricing Model in Contact Centers

There is a nightmare scenario playing out in slow motion inside enterprise buying committees.

A 500-agent contact center deploys agentic AI that autonomously handles 40 percent of interactions.

Service levels improve. Customer satisfaction rises. The business grows.

Then the CFO asks a question that is hard to answer without sounding like you’re charging rent on an idea:

If AI is doing 40 percent of the work, why are we paying the same price?

This is the practical consequence of “digital labor” entering a licensing model designed for human labor. Seat pricing assumes that value scales with headcount. Agentic AI breaks that assumption by making capacity scale with compute, orchestration, and automation coverage—none of which maps neatly to a named user.

The deeper issue is incentive alignment. With seat-based pricing, the vendor’s commercial upside is tied to the customer hiring more people. But the customer’s operational goal is often the opposite: improve containment, reduce handling time, and shift work left into automation.

That tension existed before AI, but it becomes sharper once autonomous agents are doing meaningful work.

“Investors love predictability… Consumption models are spiky. They go up and down.”

The arbitrage nobody wants to own

Here’s the part vendors often try not to say out loud: many providers increasingly buy AI compute in variable, consumption-based ways (tokens, GPU hours, LLM usage) but still sell on fixed per-seat contracts.

When AI usage spikes, costs can spike.

But revenue does not.

That creates a commercial arbitrage that can quietly eat margins, especially as autonomous systems become more capable and more widely used. It also explains why this isn’t just a procurement debate; it’s a business model debate.

Related Stories

- The Demise of Per-Seat Contact Center Pricing, and What Comes Next?

- Why Wall Street is Suddenly Nervous About Your Contact Center Vendor

- How Data Layers and AI Are Rewriting the CCaaS Market

Why Wall Street Cares: Predictable Seat Revenue vs Volatile AI Consumption

Seat pricing isn’t popular because it’s philosophically pure.

It’s popular because it’s predictable.

Wall Street understands “5,000 seats.” It understands recurring revenue tied to people. It understands renewals that look like last quarter plus a bit extra.

Consumption is different. It moves with seasonality, marketing campaigns, outages, product launches, and the very efficiency gains AI is supposed to create. It can be fairer. It can also be spikier.

That is why Zeus Kerravala’s framing lands: legacy vendors are often carrying “Frankenstein” portfolios stitched together through acquisitions, and those portfolios were priced to protect a seat-based revenue stream. AWS, by contrast, built Amazon Connect with a cleaner slate and can experiment with consumption models without destabilizing a legacy licensing base. That asymmetry matters.

“They… Frankenstein their contact center… [AWS has] an inherent advantage… because they can play around with pricing… If you were a standalone company, that would be very detrimental to the business.”

The uncomfortable implication is that pricing innovation is not just about customer fairness. It’s about which companies can survive the transition without triggering investor panic.

The Hybrid Model Emerging in CCaaS Pricing: Base Platform + Metered AI

Pure per-seat is becoming deflationary.

Pure consumption risks bill shock.

So most roads lead to a hybrid.

You can see it in how the market now talks about packaging. Even when vendors keep a “seat” concept for human agents, AI features are increasingly layered with metered credits, tokens, minutes, or usage bands—sometimes in ways that make forecasting harder, not easier.

CX Today has already pointed to the limitations of seat models: they can be inflexible, penalize efficiency, and discourage innovation. The counter-proposal—consumption-based pricing—aligns cost with usage, but it also introduces volatility that procurement teams and finance teams are trained to resist.

This is where the next generation of models is going to converge:

- A base platform fee that pays for predictability and core capability.

- A metered AI component that reflects variable compute and variable value.

- A governance layer that prevents bill shock (caps, tiers, alerts, “burst” rules).

If this sounds like cloud economics arriving in customer service, that’s because it is.

“Seat-based pricing has become increasingly misaligned with the realities of modern customer service operations.”

Why “outcomes” keep showing up in the pricing conversation

Once you accept that seats aren’t the unit, the next question is: what is?

Usage is one candidate. Outcomes are another.

Cost per resolution.

Time to first response.

Containment rates that don’t collapse CSAT.

Agent productivity multipliers.

But outcome-based pricing has a trap of its own: defining “success” is contentious, and attributing it cleanly is harder than sales decks imply. Still, the direction of travel is clear: buyers want to pay for measurable business impact, not for a headcount proxy.

The Deeper Shift: From CCaaS “Category” to Value Layers (and Why Pricing Follows)

The pricing fight is also a category fight.

As Tim Banting has argued, in 2026 enterprises may care less about labels like CCaaS and more about where value sits in the stack—data layers, AI, integration surface area, and outcomes. When differentiation shifts away from features that replicate quickly, monetization shifts too.

If UC and CX categories describe “the packaging and not the power,” then seat-based pricing becomes a kind of packaging price. It tells you how many humans are inside the box, not what the system is actually doing.

This helps explain why per-seat models feel increasingly arbitrary: the “work” is moving into layers (data, orchestration, AI) that do not map to employee counts.

“Executives and business analysts and business level decision makers are judging platforms by outcomes and not by features.”

Closing: The Plausible Future Drift of “Seats”

The likely future isn’t a dramatic collapse of seat pricing overnight.

It’s something subtler and more uncomfortable.

Seats will remain, but increasingly as a comfort blanket for human licensing, while the real value—and the real margin risk—moves into metered AI and data-driven orchestration. Contracts will start to look like cloud agreements: base commitments, consumption bands, burst clauses, governance tooling, and endless debates about attribution.

Meanwhile, the definition of “agent” will quietly drift. Not a person. Not even a bot. More like a capability that touches every interaction and changes the economics of every queue.

In that world, the companies that win won’t be the ones with the cleverest price metric. They’ll be the ones who can explain—calmly, concretely, and defensibly—why customers should pay more even as they hire fewer people.

And the companies that lose won’t necessarily be the ones with bad technology.

They’ll be the ones still trying to charge for a seat that doesn’t exist.

“They have to change to survive the AI shift. But their investors hate the change.”

Keep up with CX Today

Join the CX Today Newsletter: https://www.cxtoday.com/sign-up/

Join the CX Today LinkedIn Community: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/1951190/

Related stories:

- Why Wall Street is Suddenly Nervous About Your Contact Center Vendor

- The Demise of Per-Seat Contact Center Pricing, and What Comes Next?

If you’re seeing this pricing shift in buying cycles right now, share what questions your CFO or procurement team is asking—and what answers they’ll actually accept.

Follow the author of this story on LinkedIn

FAQs

1) Why doesn’t per-seat pricing work well for AI agents in contact centers?

Per-seat pricing assumes value scales with the number of human agents logged into the platform. AI agents can increase capacity and resolve interactions without adding headcount, so the “seat” stops matching the real source of work and cost. That mismatch quickly becomes a CFO and procurement issue.

2) What pricing models are replacing per-seat CCaaS pricing?

Most vendors are moving toward hybrid approaches: a base platform fee plus metered AI consumption (tokens, usage credits, minutes, or interaction-based units). Some are also experimenting with outcome-linked components like cost per resolution or improvements in time to first response. The goal is to balance predictability with fairness.

3) What is “bill shock” and why do buyers worry about it?

Bill shock is when consumption-based charges spike unexpectedly due to usage surges, seasonality, or operational changes. Finance teams dislike the volatility because it makes budgeting difficult and can feel like a blank check. Hybrid models often add caps, tiers, and alerts to reduce this risk.

4) Why are investors nervous about CCaaS pricing changes?

Seat-based revenue is predictable and easy to model, which investors generally prefer. Consumption and AI-driven usage can be spiky, making revenue and margins harder to forecast. That uncertainty increases pressure on vendors that rely heavily on per-seat licensing.

5) What should enterprises ask vendors about AI pricing before signing?

Ask what’s included in the base fee, what is metered, and what can cause usage spikes. Request governance controls (caps, thresholds, alerts), clear unit definitions, and example invoices under different traffic scenarios. Also ask how pricing aligns to business outcomes you care about, not just activity.

6) How far could this shift realistically go if left unchecked?

If AI agents absorb more frontline work, enterprises may scale service without scaling headcount, shrinking traditional seat counts over time. Vendors could respond by pushing more value—and more cost—into metered AI and data layers, making contracts look increasingly like cloud consumption agreements. The “seat” may remain, but mainly as a legacy wrapper around a very different economic engine.